|

| In Build a Clancy the dimensions for each part are given inline with the text, showing up in the book only when the part is used. |

Build a Clancy proudly proclaims that a Clancy is made from only 28 basic parts. These are primarily cut from marine grade plywood, with only parts like the keel, keelson, and rubrails made from solid timber. All of the dimensions for each part can be found sprinkled throughout the book; dimensions for each part are given immediately before that part is installed). This is where the plans from the New Yankee Workshop are helpful. While the drawings and the way the dimensions are given are entirely identical to the book, they collect all the drawings into three handy pages, and include plywood layouts. There is at least one error in the New Yankee plans -- 1/2" plywood is called out for the daggerboard trunk sides, but it really should be 1/4".

|

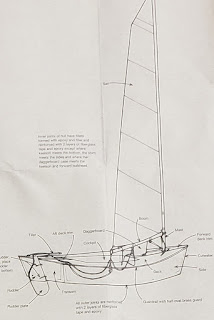

| Anatomy of a Clancy |

The plans call out for the near-mythical 4'x10' sheets of marine grade "Mahogany" or fir plywood. On undertaking the project, I had resigned myself to the idea that I would have to scarph the requisite panels from 4'x8' okoume. I was ready to submit an order to Edensaw, but, not wanting to wait the required few days for delivery, decided to call the more-local Midway Plywood to see if they have any in stock. They were out of 4x8 okoume, but it turned out that they happened to have a supply of 4'x10' meranti. It wasn't BS1088-level quality, but it was more than sufficient for my purposes.

Speaking of mythical plywood dimensions, a half-sheet of 1/2" plywood is specified for the transom and small amounts of 3/4" plywood is required for the daggerboard and mast step. I had some pieces of both 1/2" and 3/4" plywood left over from previous projects that were large enough that I did not have to buy anything. If that were not the situation, I would recommend avoiding buying 3/4" plywood and just buying a full sheet of 1/2" and using for the transom, laminating it up to 1 1/2" for the mast step, and laminating it with some offcut 1/4" to form the daggerboard. Also, for reasons that are unclear, the plans specify an aluminum rudder, but I would use the 1/2" plywood for that too.

|

| Plywood Layouts |

|

| Bulkhead dimensions |

I measured each point and marked it with a punch. The dimensions appear straightforward, though when you go to lay out the parts you find that they are unhelpfully, as in the case of the bulkheads, not all from the same datum -- sometimes you measure up from the bottom, sometimes down from the top, sometimes out from the center, sometimes in from the edge. Translating this into something easy to use is good exercise in adding and subtracting fractions.

...while stiff, long battens were used for the curves. I used a 4' long, 1/4"x5/8" cedar strip for shorter curves like the tops of the bulkheads, and a 12' long, 3/4"x3/4" strip of mahogany for the hull sides.

|

| Using a batten to connect the long sweeping curve of the bottom. You can see some unfairness midway up the curve. Some adjustment was called for to get this fair. |

After marking all the parts, it is time to make some sawdust. The bottom panels, partial bulkheads and rudder cheeks cut, ensuring these parts are identical left and right and saving you from having to mark them all individually. Long curves are cut with a circular saw...

...before switching to the jigsaw for tighter spaces.

The sheets with the deck and side panels can be stacked and cut at the same time too, as long as you remember that the bulkhead parts and deck trim are different between the two sheets. I started by carefully cutting out the cockpit area from the decks so that I could mark the bulkheads on the offcut.

|

| After bulkhead, semi cut. Do not cut the hole in the center all the way out. |

While in the swing of cutting things out, I also milled all the solid timber. The keel and keelson can be ripped to width on the table saw and the tapers at the ends cut with the circular saw.

|

| Keel |

The table saw is also the tool of choice for milling the rubrails, stem, and cutwater. The plans specify fir for some of the timber, but I used mahogany timber throughout.

When I built the Eastport Pram, I included a little bit of Solitude III in the new boat by cutting down some of the sapele from her original tabernacle into the pram's tiller. I decided that the Clancy should also have a similar relic incorporated. Having just replaced the boom gallows on Solitude, I decided to cut down the old one to form the Clancy's the knee and transom. It is fun to know that these boats are all blood relatives.

|

| Old boom gallows... |

|

| into a knee! |